Fedimint and Fedi: How Community-Run Bitcoin Mints Are Bringing Private Ecash to the Underbanked

Fedimint lets communities run their own Bitcoin-backed ecash mints. Fedi turns that into a real product. Here's how it works and who it's for.

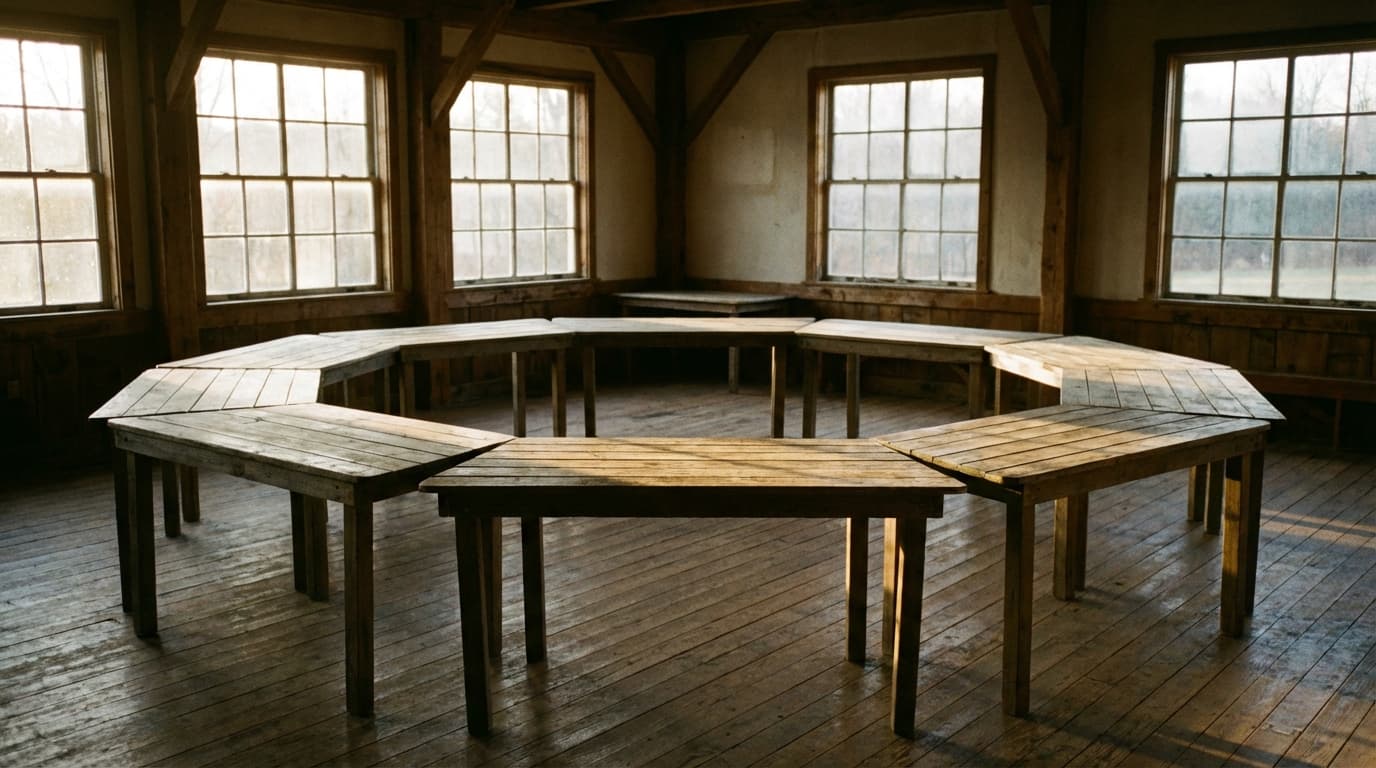

In Kenya, savings groups called chamas have pooled money and extended credit to members for generations. Now some of those groups are running their own Bitcoin mints, issuing private digital tokens backed 1:1 by bitcoin. The protocol making this possible is Fedimint. The company turning it into a usable product is Fedi.

This combination represents one of the more interesting experiments in Bitcoin's evolution: taking custody away from both centralized exchanges and the burden of individual self-custody, placing it instead in the hands of trusted community groups.

What Fedimint Actually Does

Fedimint is an open-source protocol that lets a group of people (called guardians) jointly custody Bitcoin and issue ecash tokens against those deposits. The technical foundation draws on David Chaum's 1982 work on blinded signatures, the same cryptographic technique that inspired early digital cash systems.

Here's the basic flow: A user deposits bitcoin (on-chain or via Lightning) into a federation's multi-signature wallet. They receive ecash tokens in return. These tokens can be transferred instantly between users in the same federation, with strong privacy guarantees. When someone wants to exit, they redeem tokens for bitcoin.

The privacy comes from blinding. When the federation issues tokens, the cryptographic signing process prevents guardians from linking tokens to specific users or tracking transaction histories. Your balance and spending patterns stay invisible to the people running the mint.

The security comes from distribution. A federation might have four guardians, requiring three signatures to move funds. No single guardian can steal or freeze assets. If one guardian's server goes down, the federation keeps running.

What Fedi Builds on Top

Fedimint is infrastructure. Fedi is the company building products that make it usable for people who don't care about cryptographic protocols.

Fedi's main offering is a "community superapp" that bundles a wallet, chat, and modular mini-apps. The target users aren't Bitcoin enthusiasts in wealthy countries. They're communities in Africa and Latin America who already operate on informal trust networks but lack access to stable financial infrastructure.

Obi Nwosu, Fedi's CEO, frames the problem bluntly: most people in the world can't practically self-custody Bitcoin. Hardware wallets, seed phrase management, and transaction fee volatility create barriers that make perfect theoretical security irrelevant for daily use. At the same time, centralized exchanges introduce surveillance and counterparty risk.

Fedi's answer is what they call "second-party custody." Not trusting a distant corporation, not going fully solo, but trusting a group you already know and can hold accountable socially.

Recent developments have focused on reducing technical friction. In October 2025, Fedi released a one-click federation builder tool. In January 2026, they launched a "Community Generator" to simplify onboarding. The company went fully open-source in January 2025.

Where It's Actually Being Used

The most developed example is BitSacco in Kenya, which received a Human Rights Foundation grant in 2025 to bring Fedimint to traditional savings groups. These groups already have established trust relationships and governance structures. Fedimint gives them a way to hold and transfer value with privacy and lower friction than traditional banking.

Bitcoin Ekasi in South Africa is another pilot. Fedi claims deployments in over 100 communities across Latin America and Africa as of late 2023, with expansion continuing.

The pattern matters: these aren't random groups of internet strangers. They're existing communities with reputational accountability. A guardian who tries to collude with others to steal funds has to face their neighbors afterward.

The Trust Tradeoffs

Fedimint doesn't eliminate trust; it relocates it. You're trusting that a majority of guardians won't coordinate to steal deposits. You're trusting that the federation's operators maintain their infrastructure. You're trusting the social fabric of your community to provide enforcement that code cannot.

This is meaningfully different from both pure self-custody (trust no one but yourself) and exchange custody (trust a regulated corporation you'll never meet). Whether it's better depends entirely on your circumstances.

For someone in a tight-knit rural community with limited banking access, trusting four respected local leaders with threshold signatures might be far more practical than managing seed phrases. For someone in a developed economy with access to hardware wallets and institutional custody, the tradeoff looks less compelling.

Critics would note that this model doesn't scale to global, anonymous use cases. A federation works because members can exert social pressure on guardians. That pressure disappears when guardians are strangers.

Nick Neuman, CEO of Casa (a company focused on self-custody solutions), has acknowledged that Fedimint's approach fits contexts where communal trust is the norm rather than the exception. It's a tool for specific situations, not a universal replacement for other custody models.

Technical Progress in 2025

Fedimint's core protocol continues development, with versions 0.6 and 0.7 released in the first half of 2025. Key improvements include enhanced Lightning Gateway functionality, which lets federation members send and receive payments to anyone on the Lightning Network, not just other federation members.

New wallets like Vipr.cash have integrated Fedimint support, expanding the ecosystem beyond Fedi's own app.

The Lightning integration matters because it prevents federations from becoming isolated pools. A BitSacco user in Kenya can pay a merchant in El Salvador who's never heard of Fedimint, as long as both have Lightning connectivity.

Making Sense of the Bigger Picture

Fedimint and Fedi represent a pragmatic response to Bitcoin's scaling and usability constraints. On-chain transactions are expensive and public. Self-custody is hard and unforgiving. Exchanges reintroduce the centralization Bitcoin was meant to escape.

Federated ecash offers a middle path: transactions that are cheap, private, and settled in a trust environment you choose rather than one imposed on you. The cost is accepting that trust, however distributed, still exists.

For communities in the Global South who already operate on networks of interpersonal trust, this might be a better fit than either extreme. For Bitcoiners who prioritize trustlessness above all else, it's a compromise too far.

Both perspectives have merit. The interesting question isn't which is universally correct, but which tools fit which contexts. Fedimint expands the menu of options. What communities do with that option will determine whether it matters.